‘Psychiatric collections, while they comprise evidence of past practices, are really ... as much about constructing the present and the future of psychiatry’ (Dolly MacKinnon and Catharine Coleborne, ‘Seeing and Not Seeing Psychiatry,’ in Exhibiting Madness in Museums: Remembering Psychiatry through Collections and Display, 2011, 5). If all museums are mirror to the community that hosts them as much as of the past they want to document, this is the case all the more for museums of psychiatry, which are expression of the projects, the objections, and the conflicts of current psychiatric practices, as well as reflect the expectations and assumption of society at large.

From The Bethlem Museum of the Mind

From The Bethlem Museum of the Mind

It is then for obvious reasons that the history of mental health in Europe has been long equated with the history of the Asylum, the psychiatric hospital as place of confinement, symbol of exclusion, and actual, concrete institution with its reality of bricks and fences, its organisation, its rules. These important accounts have however one lacuna: they disregard - indeed they often erase from our perception as onlookers the subjectivity, personal history, and individuality of the inmates, the patients with their experience of illness and possibly recovery. They turn them into objects – inert receivers of care, wearers of the strict-jackets we can still look at through the glass, consumers of medications, prisoners of those laces and straps we can physically see.

Elise Warriner, Welcome to my world. 1993. From The Bethlem Museum of the Mind.

At the same time, they make us, the observer, the positive of that image in turn, the healthy and wholesome possessors of rightness and understanding.

In history of medicine, as well as in reflections on medical practice, for sometimes now the claim for the ‚voice of the patient’ to be heard, and the ideal of a medicine made of patients rather than doctors, or primarily doctors, is being powerfully made. As the celebrated historian of medicine Roy Porter first spelled out clearly, a history of medicine 'from below’ is a needed project, and one that can potentially change the way we view medicine as historical product but also as social and personal activity. It is obvious that museal culture can also be deeply influenced by this shift in perspective.

One of the most famous names among psychiatric institutions in European history, ‚Bedlam’, has become proverbial and even symbolic, the 'madhouse' par excellence: the Bethlem Royal Hospital in London whose name became synonymous for chaos and madness through the centuries of its activity (from its foundation in 1247, on the land where now is Liverpool Street station in London, to its current practice as a hospital in Monks Orchard Road, Beckenham, Kent, in a green area outside the city).

Men’s Wards, St. George’s Fields, 1860 (Ink on paper, Frank Vizetelly)

From The Bethlem Museum of the Mind

In 2016 two exhibitions in London offered a great occasion to take both journeys: on the one hand, to learn about the developments of this key institution whose life spans eight centuries of European history, and on the other to stop and think about the multitude of people who made Bedlam beyond its concrete existence as institution: the countelss patients who passed through its halls and rooms, the irreplaceable individuals without whom Bedlam would not have existed. This complex history has its disturbing aspects – the confinement, the abandonment and the abuse - but also, finally, the positive ones: the healing and life one can find in the hospital now and in its more recent history.

First, there is the permanent exhibit of the Bethlem Museum of the Mind, located on the current site of the Bethlem Hospital. What strikes the visitor, once passed the entrance guarded by Cibber’s ‚Melancholy and raving Madness’, is precisely the intention to narrate the asylum through the words, minds, and eyes of patients as much as through their bodies as sufferers and receivers of medications.

The first thing one sees walking into the main space is a sequence of pictures with short comments projected to the wall, some episodic, some longer, offering testimony to the experience of various people involved with the asylum or touched by it: the patients, their families, even people who worked in the museum or the hospital, or occasional visitors. These short stories nicely allow the psychiatric hospital to appear as part of the life of many, and in a sense open destination, temporary solution, and place to leave behind. The voices of patients who return to visit after a time, sometimes after decades, recall their experience and measure their new self against the old, becoming in turn spectators and external judges.

From the Bethlem Museum of the Mind.

The space in the main room is filled with works of art of various kind produced by patients, especially paintings. Some of them are truly impressive, none is banal and the effect is to multiply once again the viewpoint behind the narration, to present a crowded humanity that cannot be reduced to any unifying label. Not only does this museum force you to think with the patient, but also to think of yourself as a patient, or as a physician, a nurse, a husband or child of an inmate; and, to ask yourself what in your life would be changed, what would remain, what different choices you would make, and so on.

In the opposite corner, another installation presents a filmed exemplary case, an anorexic patient: you can listen to her view and that of her family and doctors, as the option is posed between compulsory sectioning vs. respecting the patient’s will to be left in peace, and cast your vote by pressing a button. After listening to the short interviews the decision is much less easy than one would have thought at the start, and varies hugely from one onlooker to the other - a quick and effective lesson on the difficulty of operative psychiatry, as well as living with a mental disorder.

From the Bethlem Museum of the Mind.

Another piece makes you think in yet another direction: you can enter your own recollection of ‘words and phrases used over the centuries to describe, label or even stigmatise those with mental ill-health or disability’, which are collected in a database: crazy, idiot, fool, mad, lunatic, erratic, retard, psycho, and so on and so on, some of which are out of fashion, some other most of us have probably used in various ways; while the results run non-stop on a screen.

In a section at the centre of the space famous steps in the history of Western attempts to understand mental health are on display, such as frenology, the interpretation of mental functions and 'qualities' as corresponding to precise sections of the skull.

In another space there are the old instruments of supposed care and control, such as straps, straight jackets and drugs; an illustration recounts the far away origins of the concept of temperament, rooted in Greek medical theories about the bodily humours and their balance (or unbalance)… Throughout, however, the drawings and paintings with the thoughts and emotions of their authors remain the heaviest presence and somehow triumphs over history. The figurative art always manages to tip the balance against the narrower medicalised, institutionalised perspective - not only as museal style, but as real practice: in the recent history of Bethlem Royal Hospital patients have been encouraged to produce works of art, pieces which are then on display in the Bethlem Gallery, with this invitation to the onlooker: ‘The pieces displayed…are physical traces of a range of therapeutic, or not so therapeutic, relationships. Make your own judgement about how the artworks reveal these relatonships’.

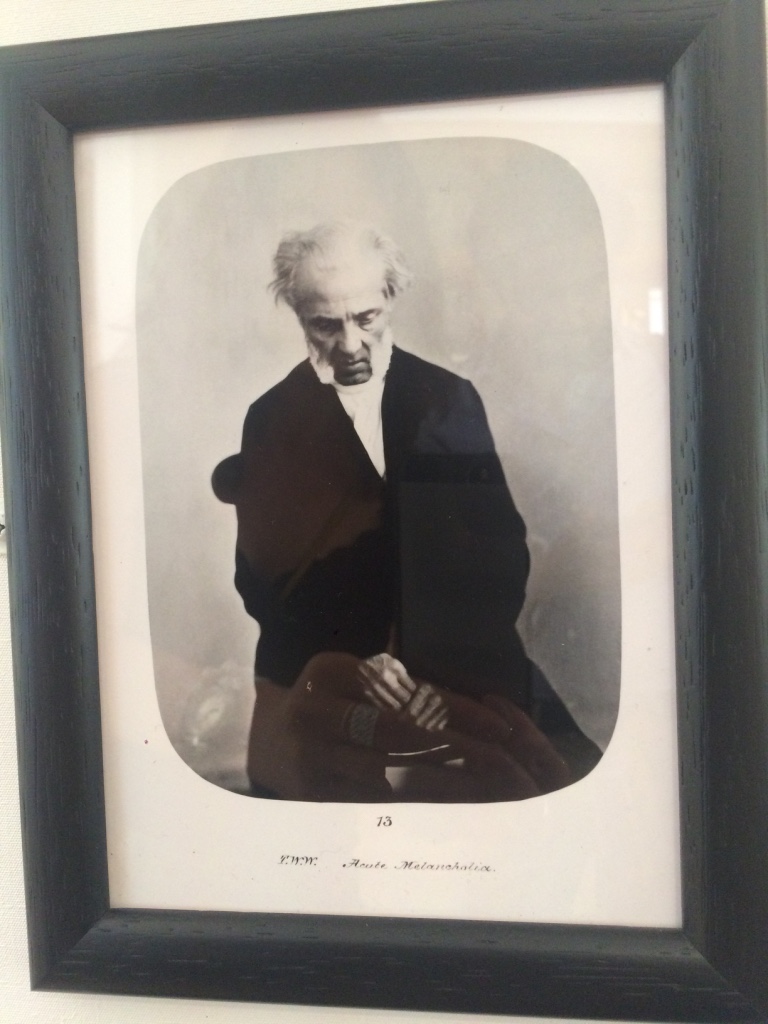

In this spirit, even the more traditional pieces of evidence appear in a new light, such as Henry Hering’s pictures of patients (c. 1857-1859), photographies originally taken with a physiognomic purpose, but here reproposed as testimonies of real life, real people and actual, precise moments, resisting the reduction to nameless asylum inmates, remembered and catalogued for the mere sake of their psychiatric state.

Henry Hering, Acute Melancholia. From the Bethlem Museum of the Mind.

The second opportunity in London to reflect about the Asylum and Bedlam is the temporary exhibition at the Wellcome Museum: Bedlam – the Asylum and beyond. There are many points of contact with the experience in the Museum of the Mind; in the exhibition space on the ground floor of the Wellcome Trust building in Euston visitors find however a denser, less structured display, mostly disconnected from any purpose to offer an historical frame. Art dominates also here; and here too, art is not the comfortable trope that casts the ‘mad’ as gifted outsiders (to see in this respect in the exhibition is the film ‘Abandoned Goods’, 2014, by P. Borg and E. Lawrenson, about art and mental patients in a psychiatric hospital). Beautiful and soothing paintings are placed next to challenging sculptures and installations that evoke constraint, imprisonment and even disembodiment, whose primary effect - for some at least - was to challenge the viewer's privilege as external, objective observer embodying the 'norm', and to expose how rapidly, sometimes unrecognisably can an object be altered by a slight change in the angle of observation.

There are individual stories and documents too: one of the strongest, most fascinating and instructive items here is a film reporting in details the process of receiving an ECT (electroconvulsive therapy) treatment, through the experience of a consentient patient - from the explanatory talk between doctors and patient to the actual preparation for the sessions, a glimpse into the routine and materiality that are the core stuff of illness and care, and yet the most difficult parts to grasp from the outside.

An important part of the collection, finally, documents various strands in the history of the ‘anti-psychiatric’ challenge – the questioning, sometimes almost the denial of any objectivity to 'mental disorder' as biomedical entity in the thought of influential sociologists and psychiatries in the last decades of the twentieth centry. 'Madness' is exposed as socially, culturally and politically constructed, partly in the spirit of Foucault’s broader critique: Szasz’s ‘The Myth of Mental Illness’ and Laing’s ‘The Divided Self’ are there, as well as the important turn initiated by the Italian psychiatrist Franco Basaglia, whose call to end psychiatric hospitalisation was made law in Italy in 1978.

In both exhibitions each visitor can find his own point of empathy, interest, understanding; or estrangement and even fear and repulsion. Rather than primarily an historical information on Bedlam the hospital, or the clinical enterprise, both explicitely aim at ‘changing assumptions about mental health’, that of others as well as one’s own and as such they reflect a wider project of inclusion and destigmatisation key in current psychiatry and social activities (examples in this sense, in the UK only, can be found even by a quick look to the websites of the association ‘Mind’, and of the foundation HeadsTogether: the fight against stigma, and the promotion of self-confidence and empathy are the priority).

Jodine Williams, ‘My mental health does not define me’ (from the ‘Museum of the Mind’)

At the end of the Bedlam exhibition at the Wellcome visitors are invited to take a card and note one's thoughts on how to possibly help, or approach in the future a person in one's life who is mentally suffering. And to fold it and take it away in one's purse. This element of awareness, listening and inner questioning, and of suspended judgement are probably quite the opposite of what mental health patients are used to finding in others, and not a small gain to take away from both visits.